Delphine Horvilleur rabbin — MJLF Directrice de la rédaction de Tenou’a — atelier de pensée(s) juive(s). Propos recueillis par Estelle Hanania avril 2015

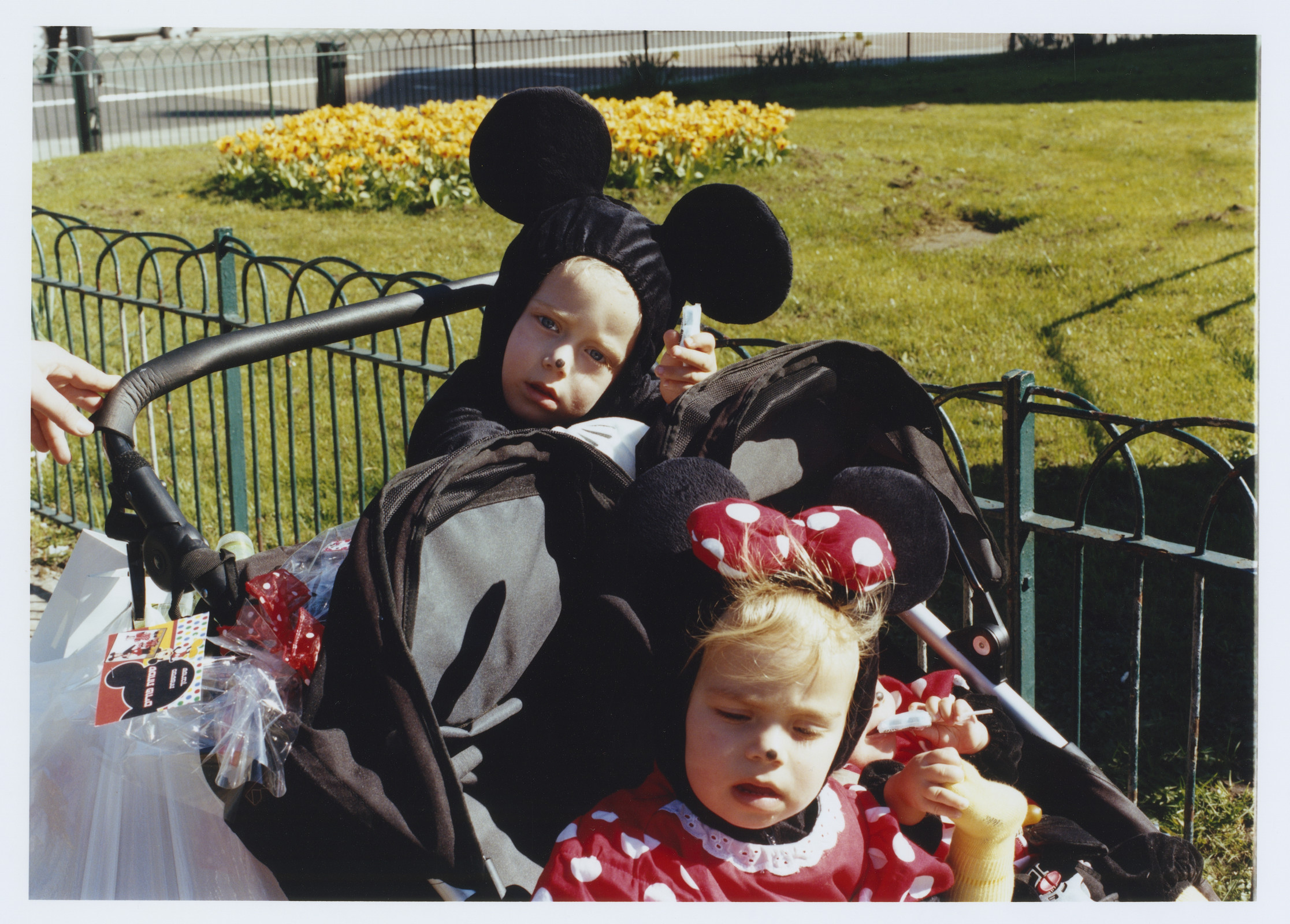

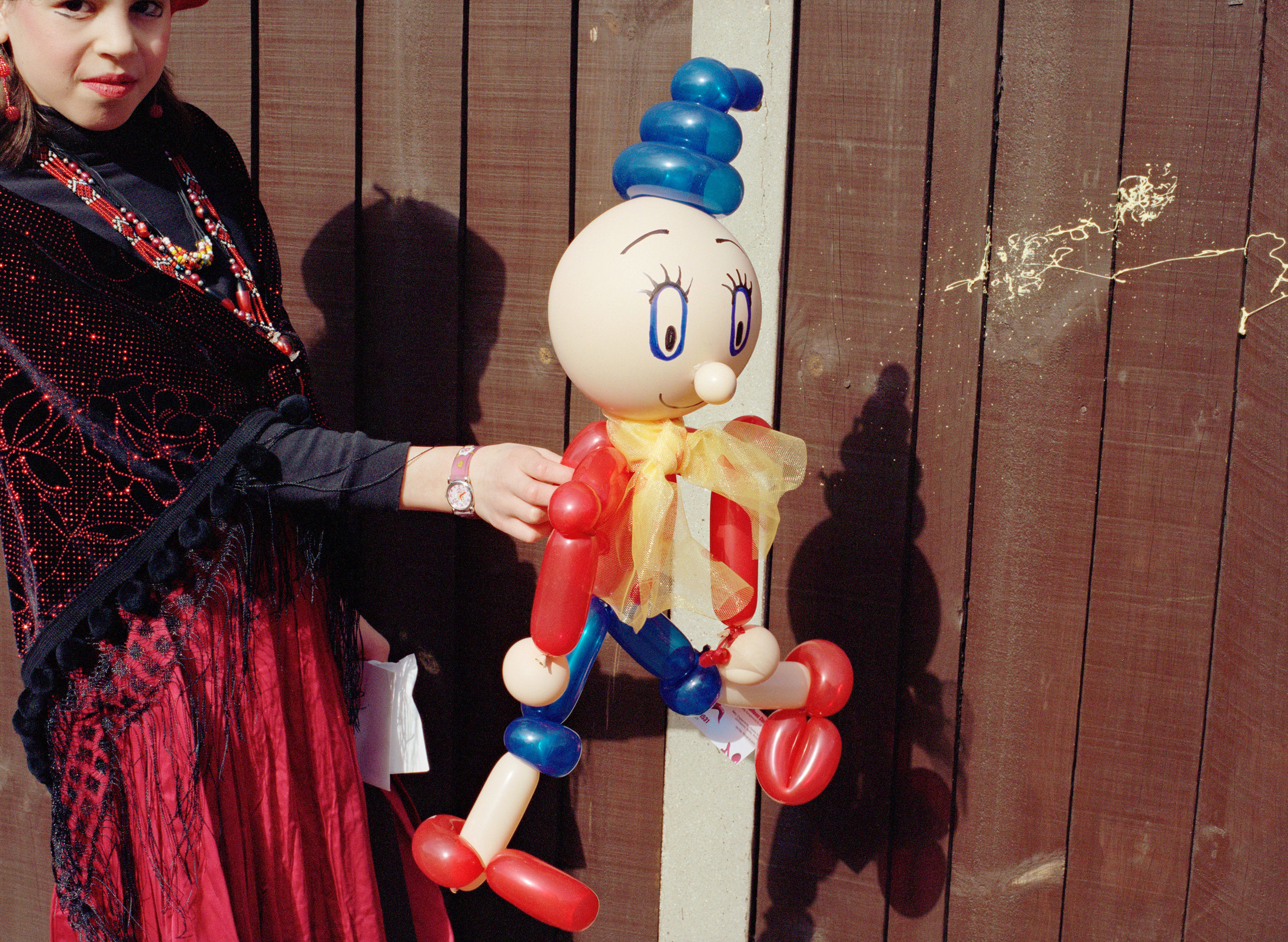

Purim has the reputation of being a holiday for children. It is children, besides, that constitute the very matter of these photos even if the truth, in my opinion, is that Purim is an adult holiday. Children, in a way, act like a veil, like the “masks” – in all senses of the word – disguising the holiday, making it up in order to hide the complex questions it raises. The fundamental issue of Purim is the question of appearance and of internal reality. On this day, we read a text called the Megillah of Esther, whose content should practically be censured for underage persons. It deals with power, violence and sex. (It is very “sex, drugs and rock-n-roll!”)

More specifically, it speaks of the power of extermination and of political force, both supplanted by a woman’s sexual power. In the Megillah of Esther women very clearly take over power and men are found in a situation of impotence (the text continuously refers to the palace’s eunuchs and to men losing all power in favour of feminine characters dominating them).

The idea of revealing what is hidden is a key theme in the story. Esther in Hebrew literally means “the hidden one” and she will, at some point, reveal herself; that is, remove the mask she is wearing, extract herself from this interiority and from passive femininity, prisoner of the gynaeceum. The wordplay is present in the term “Megillah of Esther”, “the scroll of Esther”, which also means “the revelation of what is hidden”. As for the “costume” – which plays such a particular role in the holiday – it is called in Hebrew “tah’poset” and means “to search oneself” (from the root h’apess), as if the costume spoke of an interior search: who are we? Who could we be?

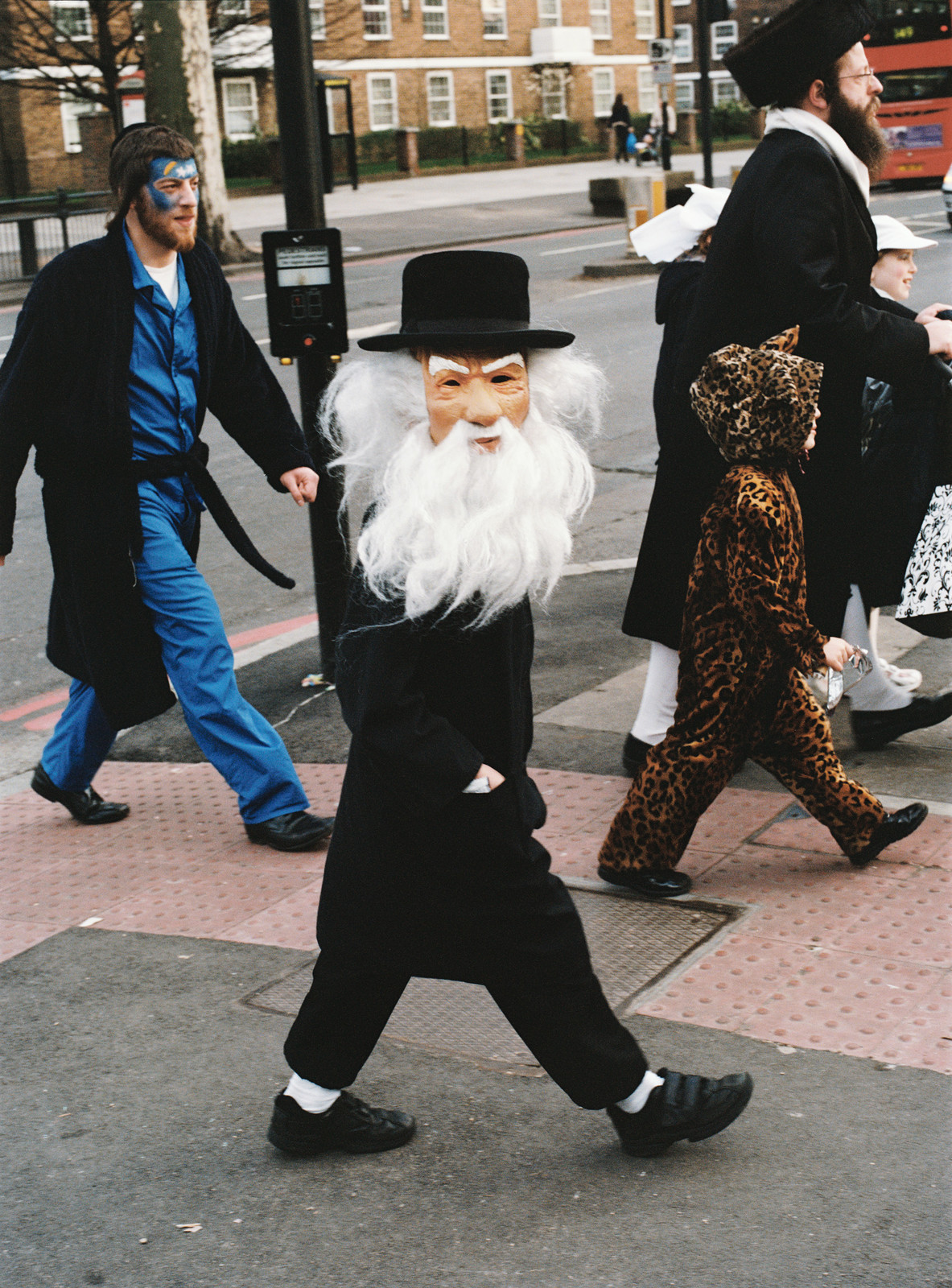

It is very interesting to see side by side, in this series of photographs, at once very classic children’s disguises that we can find mostly anywhere in the world, such as clowns, soldiers or the knight; costumes particular to a very Anglo-Saxon culture like the bobby; and at the same time disguises from the Jewish universe, like the one of the high priest, the little Hasidim or the kid dressed up as a Torah.

When we dress up, we always have the choice between dressing up as what we are not at all – typically the clown costume, image of the extreme or the excessive – or as what we would like to be, like the horse-rider for example. Unless if we dress up as what we will, a priori, become: these children that seem to be growing up in a very traditionalist world could very well one day resemble the older people they mimic, with their long robes, their “shtreimel”, these ultra-orthodox fur hats. There is always, therefore, this ambiguity: do I reveal what I am not, what I fundamentally am, what I will aspire to be, what I will become? The costume always illustrates an interrogation on identity and its possibilities.

This game of appearances poses a question that is interesting from an artistic perspective: is reality what appears through the image? Is it to be sought elsewhere? Does the exteriority of a world or of a being have anything to do with their interiority? During the twenty-four hours of Purim, we are in a zone of complete confusion, that the tradition calls “adloyada”, literally meaning “until not knowing”. Why? Because we are meant to drink, dress up and thus reverse values until it is not longer possible to differentiate the good from the bad, the kind from the mean, etc. During a whole day, we are immersed in chaos and confusion in order to be able in the end to join, once again, fully and deliberately, the established but chosen norm. The process is even more powerful in this ultraorthodox community where laws are never questioned during the rest of the year.

The photographs show adults with their so particular hats and clothes: on the day of Purim, it is impossible to tell if they are dressed up or if this is their habitual outfit. According to some, this traditional costume is a Polish, Lithuanian or Ukrainian heritage. Others affirm that, on the contrary, the costume is the remnant of a Mongolian or Babylonian traditional outfit. Whatever the true origins of this clothing, it is clear that it has come to be like a uniform of a strict orthodoxy and, most of all, an outfit inherited from the exile (one can’t imagine that Moses, descending Mount Sinai, was wearing a fur hat)

It is important to mention this topic of exile on the day of Purim because the holiday also speaks of this by asking the book of Esther’s painful question: can the Jews live calmly in exile or not? Purim gives an ambiguous answer to this question. On the one hand, Jews are threatened of being exterminated, a reminder of the anti-Semitic threat that recurs throughout History. At the same time, in the end of the book, Mordecai will become the Persian kingdom’s man of confidence – a nice model of Jewish integration in diaspora. It is not insignificant that the heroes Mordecai and Esther have Persian names, they are very clearly not called Miriam or Moses, they have names of the exile.

This issue resurfaces once more in the series of photographs. We can very clearly apprehend these characters’ integration in this British world, the ubiquity of red bricks, the typically English home entrances, etc. We also understand their integration through their choice of costume. And at the same time the question of refusing assimilation is present, through their choice of dressing up once more and of transmitting this culture to their children.

One of your photographs in particular questions the status of exiled Jews: is it foolish to be a Jew of the diaspora? Is it possible to have one’s head on straight and be a Jew in exile?

To conclude, another one of your images reflects a Talmudic episode that I find very interesting. It is this little boy dressed up as a high priest, the “kohen gadol”. He wears the outfit worn, according to the Bible, by the high priest when he officiated in the Temple. He has the pectoral, the hat, the pontiff’s tiara, etc., it is a very particularistic reference to sacerdotal Judaism and at the same time this little boy is posing in front of this very clearly English brick wall. The high priest was the only one allowed to enter in the Holy of Holies, a small room in the middle of the Temple, and I find it very amusing that he was photographed in front of this small door. One might think he is about to enter in this most sacred place for Judaism. The phrase “keep door closed” is written on the door but the door is open and it looks, in all probability, like a rubbish bin storage room… A biblical and humorous and slightly blasphemous reference… as if the Temple had been transposed to the neighbourhood of Stamford Hill and a dressed up kid was guarding its door. He invites us to laugh at our unquestioned beliefs and that is the deep meaning of this moment of carnival.