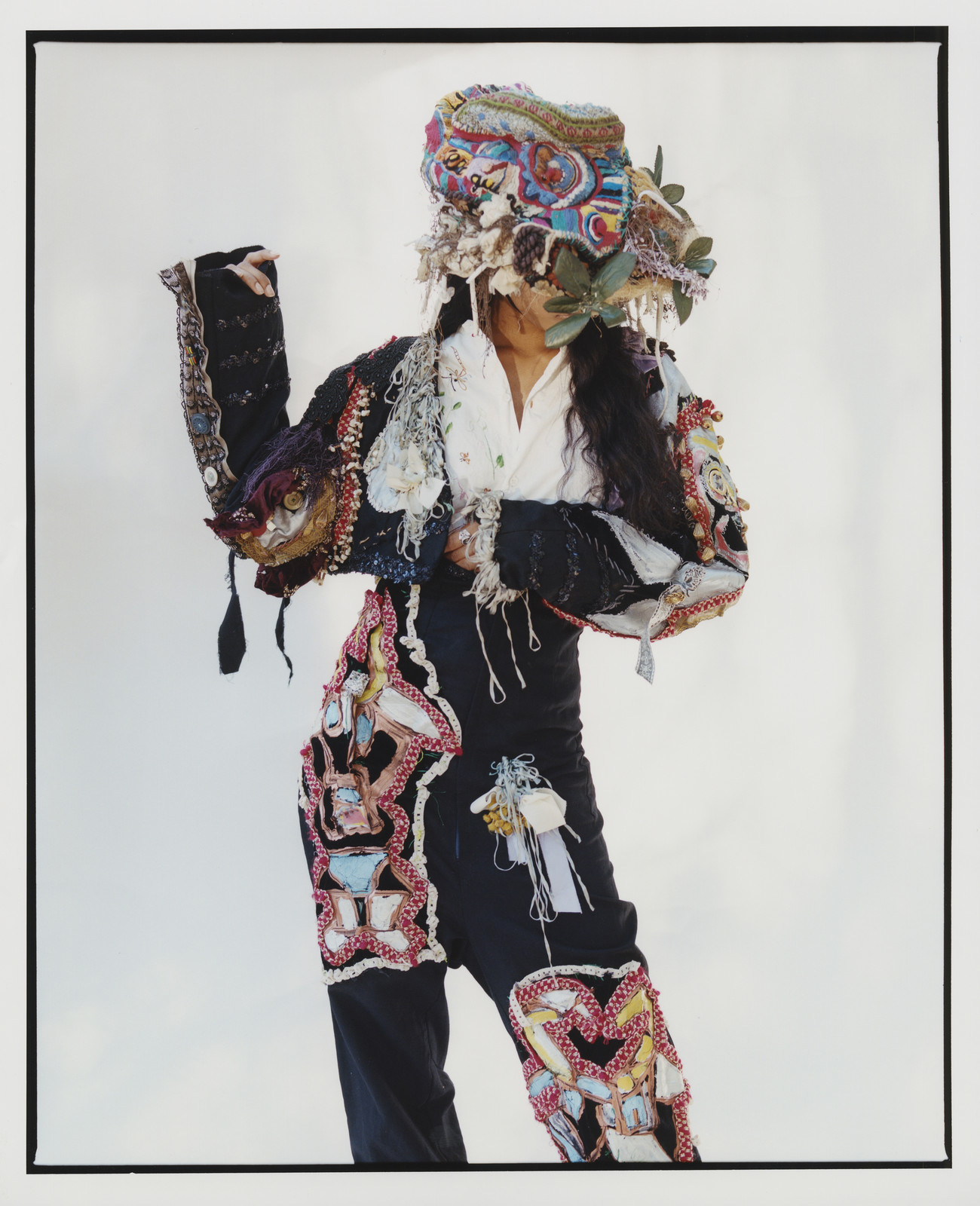

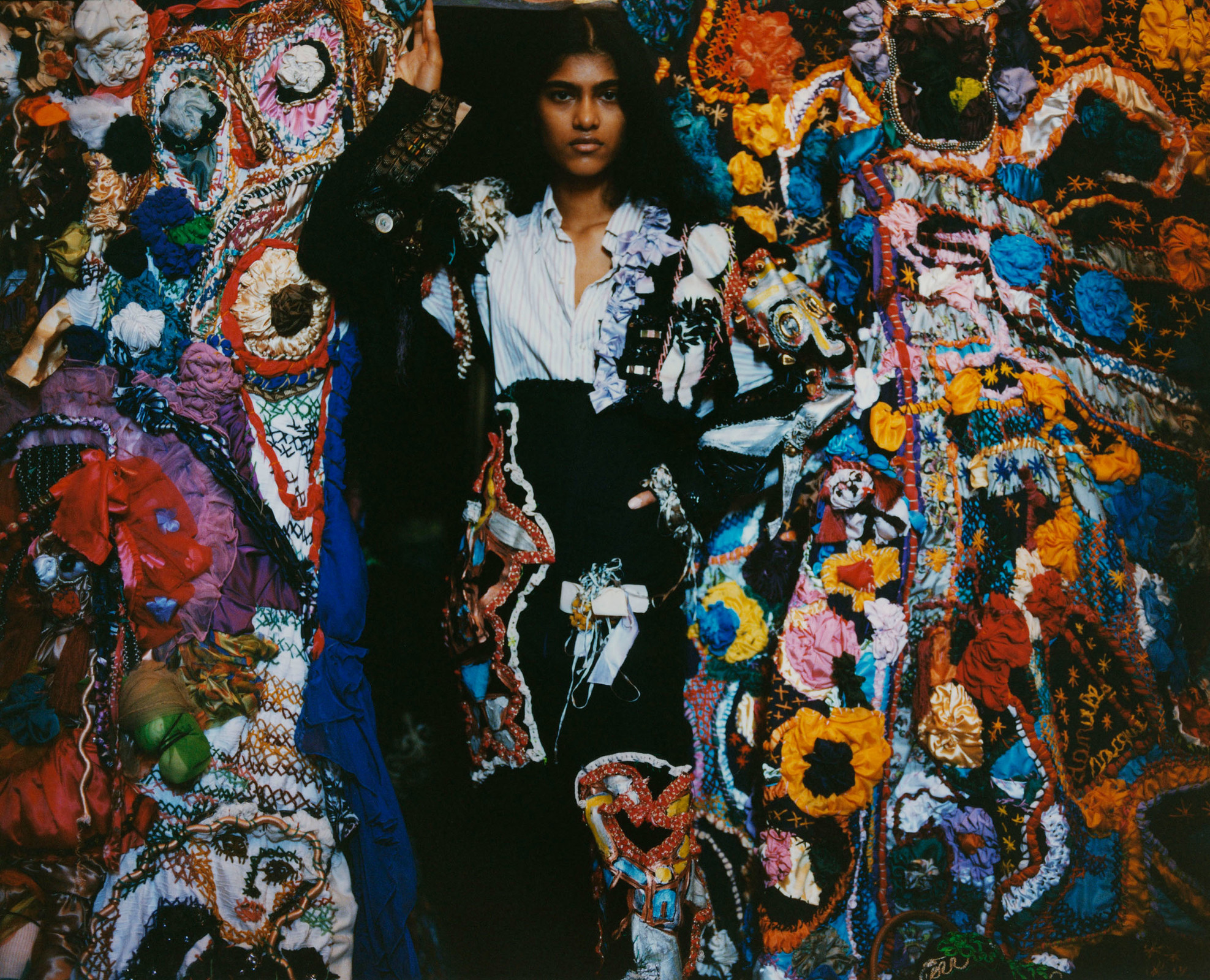

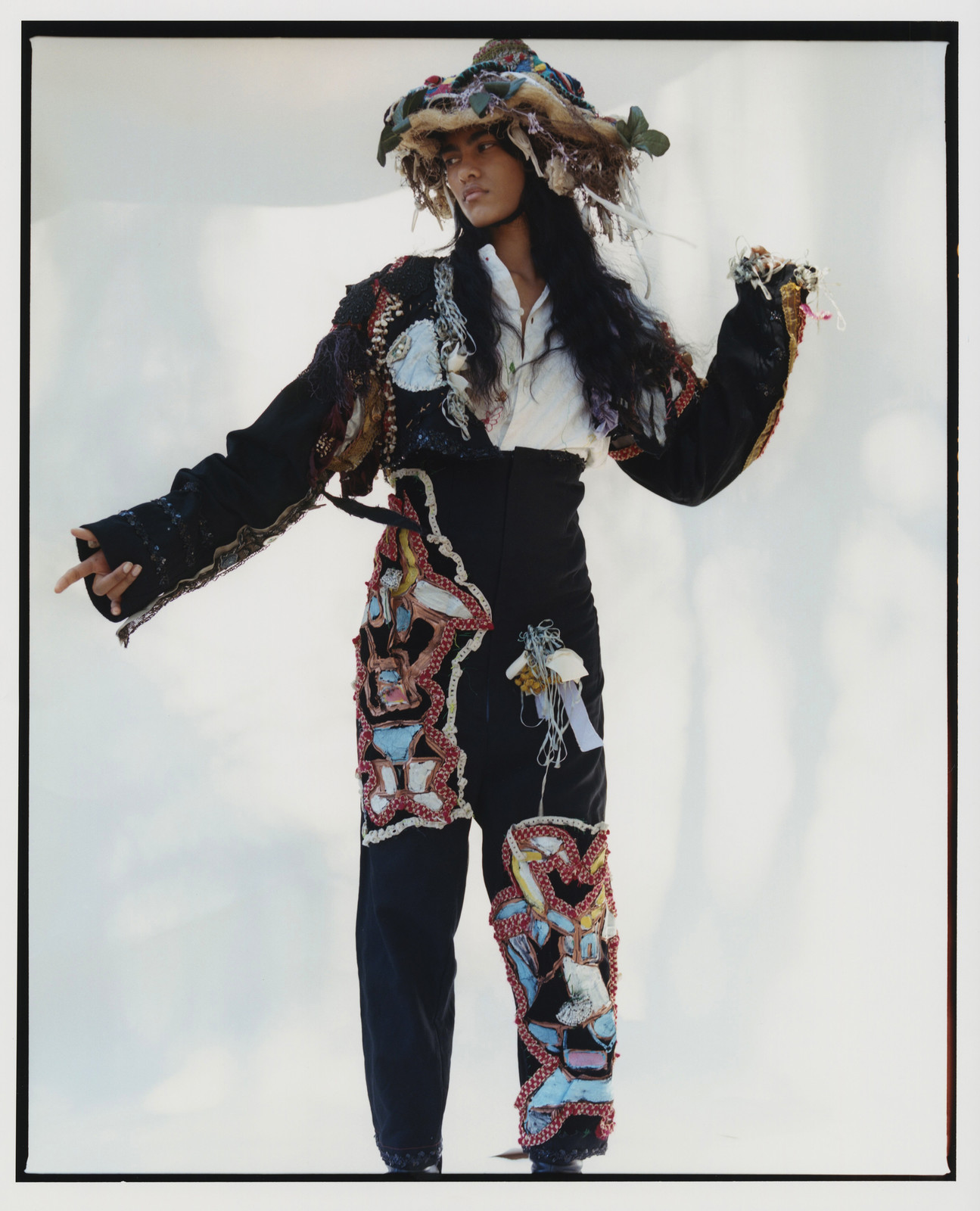

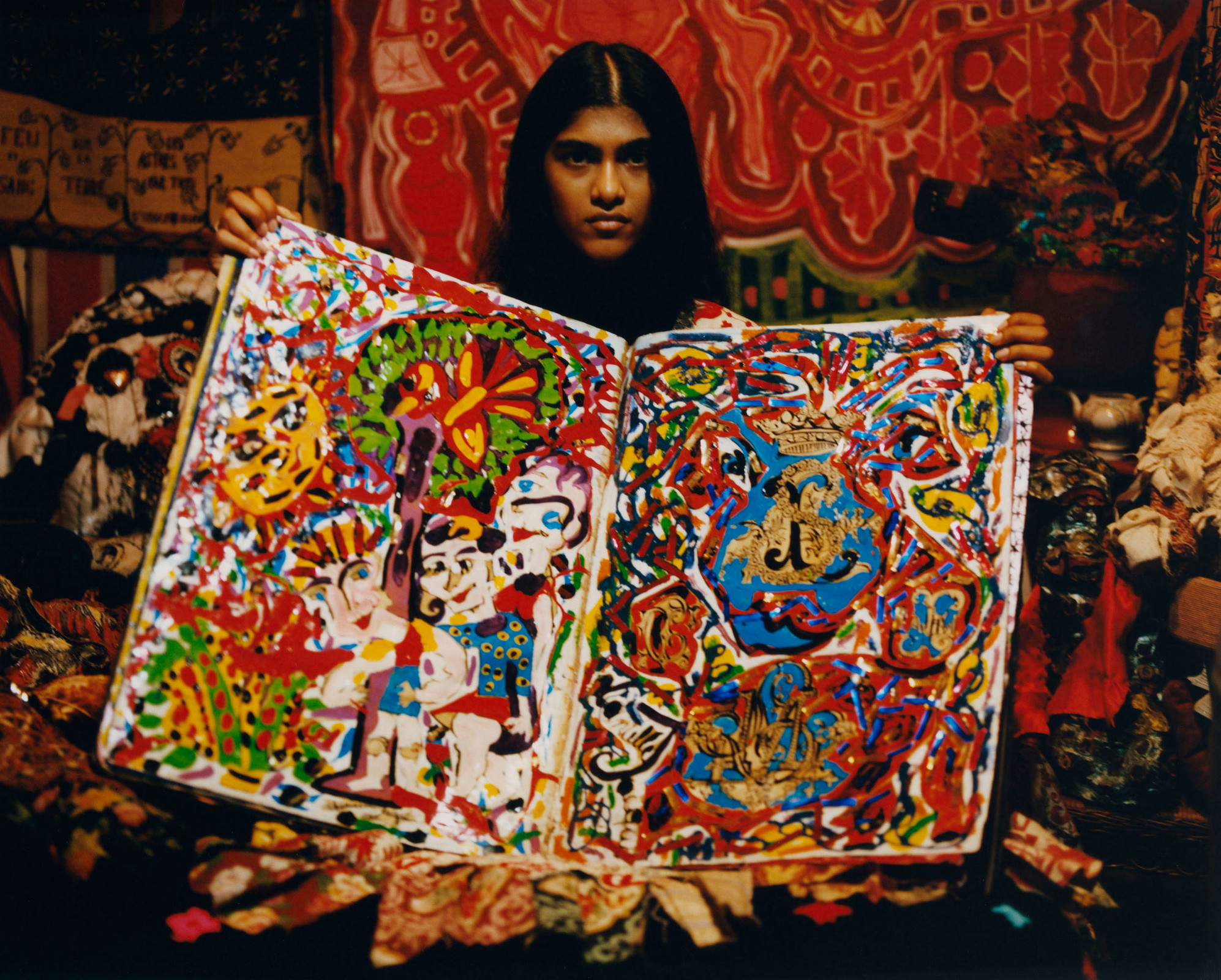

Personal story about Danielle Jacqui clothes archive

published in More or Less magazine

Editor: Jaime Perlman

Photography: Estelle Hanania

Style: Camille Bidault Waddington

Make Up: Anthony Preel

Models: Ashley Radjarame

Casting director: Piotr Chamier

Photo assistant: Clément Dauvent

Text by Alla Chernetska

La Maison de Celle Qui Peint, artist Danielle Jacqui’s house in Marseille, is not your average abode. It translates as “the house of she who paints”, and there couldn’t be a more appropriate name for the fantastical building which embodies Jacqui’s life and famed “dress works”. The past three decades have seen her decorating the exterior and interior of the house with mosaics depicting fish, animals, anthropomorphic shapes, graphic forms and small windmill wings – a colourful feast for the eyes.

Known internationally as a key figure of the Art Singulier movement, Jacqui is a self-taught creator who typifies the style’s signature of creative spontaneity over artistic intellectualisation. “I’m a maker of an artistic universe,” she explains. Beyond the house’s bright façade, Jacqui devotes her time to her textile works – dresses garnished with imaginary patterns lifted from the contents of her mind… memories and dreams made physical.

To understand why Jacqui began making these dresses, we have to look back to her early life. As a child in the 1950s, she was taught sewing at school and aged 14 was captivated by the bright gingham fabrics sold at the market on Marseilles’ Place Sébastopol. Soon after, she created her first garment, an embroidered dress with a white bodice. But things didn’t stay monochromatic for long. Her later foray into homemade patchwork gowns shocked her peers, their extreme design a world away from the austerity of postwar France. “Looking back,” Jacqui admits, “I realise how premonitory it all was. My uncontrollable urge to create was decisive and inevitable.”

In the 1970s, with a new career selling vintage clothes at a flea market, the artist returned to her youthful pastime of sewing. Already a painter, she missed being at the canvas when chained to her market stall so instead began to embroider on old shirts that she was selling. Customers would scan her stock and, rather than shop from her secondhand wares, would be distracted by the needlework she was working on. Before long Jacqui had built up a stream of admirers who would travel across Provence to see these textile works.

In the following decade, she branched into other items of clothing – designing and manufacturing them in their entirety or transforming them from prefabricated clothing sourced at garage and estate sales. A design trademark of hers was the decorative use of old buttons, preserved as non-functional works of art in themselves. Found materials remain a constant inspiration to her, as does strongly pigmented, highly contrasted colour. “I always use the same colours,” she explains “my preferred palette is like my blood type, I just can’t change it!”

Embroidering in a circular motion, Jacqui found that the technique pulled the loose fabric ground to form sculptural forms from the puckered cloth. This level of craftsmanship did not make short work though. Along with her use of fiddly mouliné-cotton threads, it heightened her meditative work process. Where others would see speed of manufacturing as the end goal, Jacqui went against the rules. Incorporating irregularities into dress and coat patterns, these off-kilter qualities morphed the silhouette of a garment once it was made up. Large asymmetrical stitches added to the sense of beautiful chaos.

Having continued her work as a painter throughout the decades, Jacqui was known for her work on canvas by the 1980s – but she didn’t want to give up sewing, her true passion. Blurring the lines between these two pursuits, she was reminded of the time her mother made her a doll during the Second World War, when cloth was rationed. In response to this, she started to create human forms with embroidered heads, the same themes of wartime personal deprivation reappearing in her one-off dresses. In her youth, the artist had never worn a communion dress nor had the chance to don a wedding dress, so she realised these unfulfilled dreams by her own making. “My dresses and coats are my protection, I used to hide my difficulties in them. By placing a finished dress in a suitcase and closing the lid, I found I could put to rest unwanted thoughts,” she says. Her 1986 Bride that Never Existed dress was made by Jacqui on the street in Carnoux-en-Provence. Formed from old potato sacking covered in embroidery, cross-stitch, buttons and trimmed with white pompoms, it drew criticism from many passers-by for its unconservative appearance. It was, however, featured in several local newspapers and caught the attention of the global media.

Fast-forward to 1998, and Jacqui made a followup to this piece with her Baltimore Bride dress, now part of the permanent exhibition at ORGANuGAMMusEum Danielle Jacqui (a new museum devoted to the artist). If, in her Brides series, the artist achieved aspirations from her past, with the Metamorphosis dress she materialised her hopes for the future. Symbolising permanent transformation and the need to renew oneself to advance in life, the dress reflects the artist’s evolution from that first shirt embroidered at the market stall. Always searching for new forms of artistic expression to bring into her daily life, it’s a fitting summary of this artist’s ongoing transformation.

Danielle Jacqui has made approximately 30 of her dresses, a selection of which will be exhibited during a group exhibition, EnlargeYourLife, at the Anatole Jakovsky International Museum of Naive Art in Nice until 9 November 2020.